Because of a Song

One of the more recent projects I have worked on is a website entitled Because Of A Song. It is my attempt to update and correct the narrative that contributes to the question “what is women’s music?”. Is there such a thing? Well, Black music does not represent all Black people. Children’s music does not represent the preferences of all children. So it is with women’s music. It is simply a slice that is flavored by a time and place in history, a point of view, a response to being underrepresented in a dominant culture. The narrative below is excerpted from the Because Of A Song site with the hope that it encourages you to view the 23 interviews with remarkable feminist and lesbian feminists, the beautiful photos of artists from the 1970s on, the listening room with playlists of women and their music over the years, a reading room full of fascinating resources, and more.

I hope you enjoy this jampacked and enjoyable journey – it is free. Go to becauseofasong.com and enjoy.

Because of a Song

omen’s Music is a phrase coined by lesbian feminist singer/guitarist Meg Christian in the early 1970s.

Every social change movement has a music. This flowering of Women’s Music did not come simply as a search for lesbian romance and beautiful harmony, although that would have been reason enough. It exploded out of a deep rooted need to combat homophobia and sexism and to build safe community. The performers reflected back to the audience women as real people—an honest, authentic expression of woman identification—how women saw themselves as feminists and lesbian feminists—something they had not been able to do in the mainstream music industry at that time.

In conversation with Ginny Z. Berson, co-founder of Olivia Records, Ginny said, “Women’s Music activists were refusing to be defined by men and insisted on defining themselves. This included designing space in which women artists were unrestricted and the audience could see themselves without fear of a system intent on forbidding this freedom of expression.”

Women instrumentalists who had been the one female in all male bands or who couldn’t get into those bands at all, started forming their own groups. Some were recovering from horrific treatment on the road as the only woman on the tour, constantly fending off unwanted sexual expectations. In the work with women, there may have been romance but it was not aggressive or demanding. There was a different dynamic at rehearsal; players seen and heard, ideas respected. Space opened up to investigate the female in style, rhythm, lyrics, volume, communication, and process. Touring with a large ensemble was expensive, so many groups settled into the Oakland music scene playing in the women’s clubs and bars but also in the main music venues—booked because they filled the seats! More women were showing up, buying tickets and drinks, and dancing with each other. As women’s music changed, so did Oakland.

In 2019, long before the idea of an archive had emerged, Holly Near (singer-songwriter, record producer, and curator of this site) interviewed four women who played an integral part in shaping the narrative of Women’s Music on the west coast of the United States. She knew they had each walked through very different doors to arrive at their elder status in the world of Women’s Music.

Women-identified songs were ushered in by thousands of women across the nation and the world, often crossing boundaries and borders on cassettes to be shared in the privacy of a room, a van, a women’s center. And in a rather short period of time, these bold songs were sung at Carnegie Hall in concerts produced by the late Virginia Giordano.

Oakland California was its own little Paris with watering holes like the Brick Hut, Ollie’s, A Woman’s Place, and Mama Bear’s. Why Oakland? Tess Hoover, a tax accountant who became one of the go-to lesbians for issues of money, taxes, and nonprofits said, “The music isn’t necessarily why we came but it is why we stayed,” making Oakland one of the most vibrant feminist, lesbian feminist, and multi-cultural communities in the country.

Inspired by the first interviews, I asked more women to meet with her in conversation to discuss Women’s Music, racism, craft, heartbreak, sex, geography, disappointments, education, and revolution.

Conversations with these iconic artists are in the Conversation Room of becauseofasong.com

The Because of A Song archive is focused specifically on women who intentionally left the mainstream music industry to build a new vision for women. Connected to life’s daily conditions, this music turned many women from victims to warriors. There is no way to register the immense influence this music had on the expansion of feminism as well as the effect it had on the mainstream music scene, politics, health care, education, sports, fashion, the fight against racism, language, global solidarity and family relations.

It was not planned nor did it have a clearly articulated direction. It was a response to having been abandoned by family, considered mentally ill, refused high paying jobs, rejected by mainstream recording companies (for being out or outspoken), for challenging the fashions of the traditional female image. A community was built—one that was predicated on what could be both a solid and fragile relationship between artists, activists, presenters and audience. We were all new at becoming ourselves.

The lesbian bars and softball leagues had created a space for lesbians to gather. And then with the creation of lesbian identified songs, women flocked to the concerts—to see and hear themselves projected from the stage as well as to find one another in the audience. The lobbies were filled with tables introducing organizations, actions and future events. Some women had never heard a lesbian lyric, nor had ever been in a crowd of beautiful vibrant out lesbians. Whether 20 women in a small club or 1500 women at a big theater, these were life changing gatherings. Some came in full dyke regalia and others in disguise so as not to lose their day jobs if spotted—in particular, women from the military.

For this archive, I spoke with artists, thinkers, peers, and friends. They discussed craft, the high notes, the music scene, body shaming, songwriting, touring, money, leadership, mental health and resistance—and there was laughter.

From the Curator: Holly Near—curator, producer and host of Because of A Song

It has been a great honor to work on this archive. And humbling. None of us knew everything. We all knew something. The generations before us knew what they knew and we improved on it. The next generation will pick up from where we left off. That is how it goes. We have left a huge legacy of knowledge there for the taking. The archive is a small piece of it.

Were mistakes made? Yes. Was it an incomplete investigation? Yes. Were there things we didn’t understand? Yes. White women didn’t know much about racism. Middle class women didn’t know much about class. Able bodied women knew very little about physical difference. Oppressed people were pulling themselves out of centuries of abuse. Still, internalized oppression does not depart willingly. We were unpracticed at coalition politics. We had to feminize all the previous theories about systemic oppression.

This extraordinary flowering did not get birthed in a perfect state. It was messy. Exclusive. Inexperienced. Underfunded. And because of its strong lesbian feminist identity, it was often rejected, criticized, made fun of, feared, and perhaps worst of all, ignored.

Having been vilified by one’s own parents kept many women occupied with their personal struggles. Parents dragged kids to psychiatrists when homosexuality was considered a mental disorder. Lesbians’ children were taken away and given to straight people. Dykes were beaten in alleys outside of the women’s bars and tires slashed.

In or out of the closet, most women were struggling to get equal pay. Their bodies were humiliated by doctors. They were living in marriages that traumatized their hearts and safety. Raising children without support. Women from multiple cultures had multiple issues with which to contend.

So it made sense that lesbians began to build an alternate culture. Many women went to Laney College for $2 a credit to learn carpentry, auto repair skills, bookkeeping and hair cutting. A barter and trade economy was informally put in place. Women shared cars to get to events and rallies and lived together in big houses no one could afford if they were on their own. Women prioritized their hard earned cash. Time and time again, they bought tickets to lesbian cultural events—not just once or twice a month but multiple times each week! Lesbians called themselves Lesbians keeping pressure on government, media and the gay movement to end the stigma of invisibility. All this without cell phones, internet, or Facebook. It was an in person, up close and personal political movement.

However, to this day, most books/articles/lists skip over women’s music. Looking online for lists of lesbian songs, one is hard pressed to find any artist from women’s music included.

The surface is barely skimmed in this research, but one thing is certain—the women’s music that came out of Oakland, CA was at the tipping point of the feminist revolution in the 1970s. The music continues to this day challenging inequity, building and sustaining community, supporting local artists, uplifted by national treasures and connecting with global activism.

Women’s Music is a concinnity of sound: orchestras, big bands, choirs, rock bands, jazz quintets, drum ensembles. The story includes artists, producers, photographers, sound engineers, graphic artists, music distributors, arrangers, managers, agents, audience, and You.

AND there were dancers who choreographed to Women’s Music as their primary material.

AND there were poets who had a major influence on the music community. We could not have had such illuminating conversations were it not for Maya Angelou, June Jordan, Audre Lorde, Angela Davis, Alice Walker, Adrienne Rich, Joy Harjo, Cherri Moraga, and Oakland’s own Pat Parker and Judy Grahn. We built on their work.

AND there were organizers and bookstores, coffee houses, restaurants, and all over the world an explosion of press collectives and newspapers—all part of creating space for lesbians—all before cell phones and social media. And the audience that chose again and again to spend what little extra money they had on women’s music. That was so essential. These women were the glue. Without this glue, Women’s Music would have come unstuck.

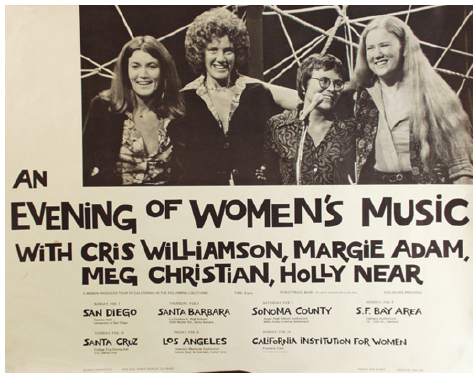

There is no doubt that Meg Christian, Margie Adam, Cris Williamson and I made the first highly visible splash on the pallet of Women’s Music and lesbian culture. A half-hour documentary was made in 1974 called Come Out Singing produced by Lynne Littman (see reading room). It was aired on PBS Los Angeles and Lynn won a local Emmy for her work.

The Women on Wheels Tour in 1975 was performed in large venues in seven California cities. The tour introduced woman-identified music to thousands of people and was noticed by such media outlets as Rolling Stone magazine. Marianne Schneller put up the initial funding, which she borrowed from her father. She was a valiant producer along with dozens of women who joined in—donating their time and skills to make this tour happen. It was a pivotal moment in the evolution of what became known as “Women’s Music.”

Alix Dobkin from New York (Lavender Jane Loves Women) and Maxine Feldman from Los Angeles (Amazon Women) led the way to writing the most specific and out lesbian songs. And Cris Williamson’s inspirational Changer and the Changed, released in 1975, has sold over 500,000 copies and continues to sell to this day.

All-women record labels, distribution companies, and concert promoters sprouted up across the country and in many other English-speaking countries. In Chile, once the Pinochet dictatorship was brought down, Chilean women singer/songwriters began to investigate feminist music.

The fact that there seems to be a new curiosity about the work is welcomed. And it is never too late (for the living nor for posterity) to try to tell the truth.

I encourage us all to take something away from each artist that might elevate our own work, our own sense of the artistic process, our collective understanding of how social conditions and geography define our contributions.

The telling of a story starts with a point of view. History is not a fact. It happens. And then, it is in the telling and retelling of the stories that we come to understand events, ourselves, and each other. To tell the story of feminist, lesbian, woman identified music, what came to be known as “Women’s Music,” requires multiple voices and genres.

“One thing is clear. No matter where we come from or what our experience, if we don’t see that feminism means all women, then it doesn’t work for any of us.” -Ginny Z Berson

We who love Women’s Music, we whose lives were changed by its very existence, are now able to document it as accurately as possible from all corners of the world, each contributing what she knows and archiving collective knowledge/memories—leaving it somewhere to be discovered.

December 2021

P.S. We end with a kiss.

A Note From Holly

I benefited as activists from the accessibility movement educated us about their lives and needs. They demonstrated for access to buses, accessible curb ramps, interpreters in courts and hospitals, and accessible housing. My sister Timothy, who was working with the National Theater of the Deaf, signed one of my songs for me. That inspired me to bring this ever-growing awareness to my audience. Because of A Sign tells a small part of that story. And then my interview with Candas Ifama Barnes shines a light on the future of American Sign Language with our contemporary understanding of what it means to be culturally sensitive in any language.